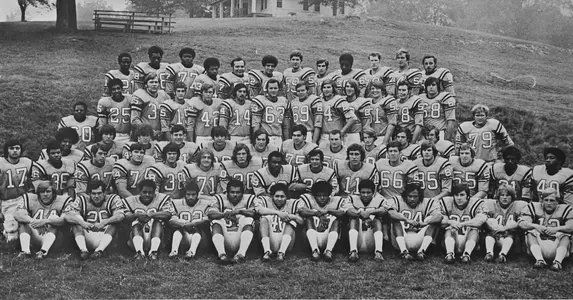

Photo by: Columbia University Athletics

1971 Columbia Football: The Cardiac Kids

9/23/2021 7:00:00 AM | Football

Game Preview1971 Photo Gallery1971 Season Statistics (PDF)Columbia Mourns the Passing of Frank Navarro

50-Year Tribute: Remembering the 1971 Columbia Football team that finished 6-3 with seven straight games won or lost by three points or less; Members of the team will gather for a reunion prior to Columbia's game vs. Georgetown.

Note: a shorter version of this story will appear in Saturday's game day program.

NEW YORK—With six seconds left in the game, the cork was halfway out of the champagne bottle in the Columbia press box.

"It felt like the longest six seconds of my life," recalled long-time Columbia sports information director Kevin DeMarrais.

But when Princeton's kicker missed the 32-yard field goal attempt on October 2, 1971 at Baker Field, and the Lions won 22-20, Columbia's 26-year losing streak against their hated rival was over, and thus began the life of the "Cardiac Kids," the moniker DeMarrais was to give them for their seven straight games won or lost by three points or less in that storybook 1971 season, a record that was unmatched for 50 years in college football at the time.

"Over the years, we won the Rose Bowl, we lost to Princeton. We won the Ivy League title, we lost to Princeton," DeMarrais said, remarking on how big this first victory since 1945 over the tigers was.

"We were always confident we could win," said Frank Dermody, Columbia '73, a long-time leading Pennsylvania Democratic state legislator, and one of the three mega-talented linebackers on that 1971 team, said about the Princeton game, and the 6-3 '71 season.

Remember, this is a school with a less than fabled football tradition, that had come off of a 3-6 record the year before and a 1-8 season two years earlier, despite having been led by quarterback Marty Domres, a first-round NFL draft choice in 1969 (and just the most recent in a string of gifted Columbia quarterbacks that included Sid Luckman and Archie Roberts.)

And this was a Columbia University still reeling from the campus protests of spring 1968, the result of a volatile cocktail of anti-Vietnam War and anti-University administration feeling, that led to the occupation of Hamilton Hall and violent confrontations with police that received negative national media attention damaging to the University.

"It was total chaos trying to get back from '68," said Lila Coleman, widow of popular Dean of Students Henry Coleman, who was shot five times in his office, (but recovered), in 1972 by disgruntled student Eldridge McKinney – who has never been found.

In 1971, "Columbia was still limping along," remembered English professor and long-time associate Dean Michael Rosenthal.

And New York City, of course, is always inextricably linked to what Columbia is, and New York in 1971 was an exciting but not always safe place.

"I was held up at gunpoint near Ferris Booth Hall, and my room was broken into at my frat," recalled star quarterback Don Jackson, '73, a New York kid who had gone to the city's prestigious Stuyvesant High School. "But since I knew the city, for me it was business as usual."

For defensive back Steve Woods, '73, from Indianapolis, New York was more than he had hoped for. "There was so much going on culturally…you had Harlem, you had a plethora or museums. You got to meet James Baldwin…everyone came to campus."

Columbia sports, however, were a mixed bag. Basketball had been big on campus, with a nationally ranked team in 1969 led by future NBA star Jim McMillian and future Rhodes Scholar Heyward Dotson. But not football.

Football tight end Mike Jones, '72, recalled Dotson looking at him in the elevator one day and derisively saying, "You guys play football?"

The 1971 football team did more than a little to heal the wounds of 1968, and bring together the students, faculty, administration, (and even perhaps the city) in a time of nation-wide anti-war protests, emerging and long overdue but sometimes fitful gains for women, blacks and gays, and cultural changes not seen in decades – if ever.

Some Columbia Spectator headlines from the fall of 1971 give a pretty good idea of what was going on at the time:

Oct. 8 "Trustees consider election of woman to board vacancy" (no woman had ever been named to Columbia's board of trustees at that time)

Oct. 14 "Architecture panel considering Black as dean of school"

Oct. 15 "Latins to File Suit Against University

Nov. 3 "(Dean Carl) Hovde Affirms Position Opposing Gay Lounge"

Nov. 8 "Thousand Rally Against the War"

Nov. 15 "Women Asked to be Included in Negotiations on Sex Bias"

Gallery: (9-23-2021) Gallery: FB | 1971 Tribute

The '71 team was by a diverse group that was close then and has remained close for 50 years, many of whom had other options of where to play.

Middle linebacker Paul Kaliades, ' 73, from Snyder High School in Jersey City, who received a vote for the Heisman Trophy, got "full ride" offers from Nebraska, Syracuse and others. Co-captain John Sefcik, '72, from Ohio, turned down Princeton. Defensive backs Charlie Johnson, '72, another co-captain, and his Arsenal Technical High (Indianapolis) classmate Woods, could have gone to Purdue and the Naval Academy, respectively, though as Woods put it, "once you graduated from the Academy, your ass went straight to Vietnam." Quarterback Jackson, a skinny kid from Stuyvesant, turned down Notre Dame (and had come to Columbia because of Marty Domres. The attempt to tag Jackson with the nickname "Amsterdam Don," to compete with New York Jets QB Joe Namath's "Broadway Joe," as a nod to Columbia's other bordering avenue never quite caught on.)

(That class also featured a pretty good running back named Ed Harris, a friend of this author, who dropped out after two years, but seems to have fared well in his chosen career of acting, and another 1973 classmate, Eric Holder, who became US Attorney General under Barack Obama, Columbia '83.)

One thing they all shared in 1971 was the belief they were a talented team that could do anything.

"I went into that season thinking we had a good shot to run the table," remembered Kaliades.

"We were committed to one another," said Johnson, now retired from a career on Wall Street. "There were no challenges we could not meet. And we did."

The season didn't begin auspiciously, with a 3-0 loss to Lafayette, and for a moment, there was a "here we go again" feeling. Just for a moment.

But then came Princeton, a convincing, if nail-biting win, with Jackson connecting to (the late great) receiver Jesse Parks, '73 on key plays and defensive back Ted Gregory, '74, returning an interception 56 yards for a touchdown.

The following week was a heartbreaking two-point loss at Harvard, which several players blamed on the play calling of head coach Frank Navarro, who died this spring, and for whom there is little love lost among many of those interviewed for this piece.

Even in losing, things could be entertaining, with Columbia's famed band livening things up. James Minter, '73, a thirty year veteran of the admissions office and band member, recalled the band planned to take their pants off at a Harvard game, until someone said "You don't take your pants off at Harvard," but did fondly remember a "Martyr" halftime show where the band honored Joan of Arc by forming a French fry and playing the song "Light My Fire," always trying to get whatever they could past Dean Coleman, whose task was approving band scripts.

But on October 16, at Baker Field, the Cardiac Kids came roaring back.

Trailing 14-0 against Yale, the Lions surged in the second half thanks to a long kickoff return by Sefcik, and a touchdown pass from Jackson to Tom Hurley, '73.

With less than two minutes left, Jackson threw another TD pass, this time on a great one-handed catch by Bill Irish, '73.

Jackson had been calling offensive plays all season at this point, and called a two-point conversion play, an option pass to be thrown by the 5'7", 155 pound Sefcik – often the last man on the field in practice - to tight end Mike Jones.

Sefcik recalled Jackson saying to him before the play, "You better not screw it up, Mouse."

And he didn't, completing it to the wide-open Jones for the 15-14 last-minute victory.

Jackson called the Yale game "the most electrifying win," and calling Sefcik his "favorite player ever…nobody tougher," and that play for that two-point conversion "the crowning moment of my career," – quite a statement from a guy who was selected to the All-Ivy backfield with Cornell's Ed Marinaro, Yale's Dick Jauron and Princeton's Hank Bjorklund, as Jackson said, "three NFL guys and a skinny guy from New York."

The next week, Columbia beat Rutgers – again by one point – 17-16. It's hard to think of beating Rutgers as a footnote, but in the 1971 season, it was.

Then, they went to Cornell, to face the 5-0 Big Red, featuring the fearsome (future actor) Marinaro, who would finish second in Heisman Trophy voting that year, behind Auburn's Pat Sullivan (it's okay to say "Who?")

The Lions lost another close one, 24-21, as Marinaro rushed for 272 yards, breaking the then-standing NCAA rushing record. (Kaliades played with a fractured arm taped to his chest, but considering how strong Cornell was, Columbia kept it close.)

By now, fans were showing up at Baker Field. Not in droves, but showing up.

Eileen McNamara, Barnard '74, Journalism '76, a Pulitzer Prize winner and key figure in the Boston Globe's reporting on the Catholic priest molestation scandal, admits, "I probably didn't know Columbia had a football team," but she was a floor counselor and knew some players and that the team was successful in 1971, and began going to games.

Lyle Rexer, '73 a swimmer and Rhodes Scholar and transfer from the University of Michigan, said, "That team got me to go up to Baker Field…I liked watching them because it was the complete opposite of Ann Arbor."

Then Dartmouth came to town on November 6, sporting a 15 game winning streak and a lot of attitude.

Every communication to the Columbia players the week before that Dartmouth game started with the numbers "55-0," a bleak reminder of score of the 1970 game in Hanover.

Steve Woods recalled the 1970 game. "Every time they scored a touchdown, they shot off a cannon. There was so much smoke in the air, it looked like Waterloo."

The Lions all came in wearing white shoes as a morale booster, and brimming with confidence.

"We knew we could win against Dartmouth," said Mike Jones.

But it was a back and forth game, with the Lions leading 28-14 in the third quarter, only to see the lead disappear. Dartmouth went ahead 29-28.

Jackson marched the team down the field to set up a 34-yard field goal attempt by Kaliades with 48 seconds left.

Kaliades remembered saying to Jackson, who was also the holder on kicks, "Don't give me the f…ing laces" meaning the laces of the ball to kick, to which he said Jackson replied, "Shut up you fat f..k, just kick it."

As Jackson also noted, "most kickers come in with clean jerseys. Paul was beaten to death," having played the whole game at middle linebacker.

Kaliades made the field goal, a famous "wounded duck," that just cleared the cross bar, giving Columbia a 31-29 win – a story that made the front page banner headline of the New York Times sports section.

Columbia won their next two games by 14 and 18 points, finishing 6-3, third in the Ivy – not what they had hoped, but a long way from recent finishes.

"What I remember most about that season is we had so many heroes, so many stars," said sports information director DeMarrais, adding, "'71 helped us forget about '68."

Some of the guys were political during that era. Most weren't. George VanAmson, '74, a back-up player who described himself at 5'4" as "the smallest man in Ivy League football" his three years, and who later became a Columbia Trustee, said he was "very wary" of demonstrations on campus. "I was not a front line demonstrator, though I passionately agreed with it," noting that the "rich white kids" had other options if they got thrown out of school, but "I didn't."

Kaliades recalled a professor telling him "You are the first Columbia football captain who ever participated in shutting down a building here."

Nearly all the players have fond memories of that season, of their teammates, and of Columbia.

Going to Columbia was "the greatest decision I ever made, said John Sefcik.

"The Columbia brotherhood of football players is amazing. Columbia football is amazing," remarked Don Jackson.

"The Columbia backbone and bonds extend through generations."

"Even 50 years later, we still have that camaraderie," said Steve Woods, who noted that not long ago, Kaliades came to visit him in South Bend to see a Notre Dame football game.

"The greatest team in Columbia history was our team," offered Charlie Johnson, adding, "We brought excitement on Saturday afternoons in the fall," adding that being at Columbia was "One of the greatest experiences of my life."

Several of the players noted that institutional support for football was lacking when they played, but that seems to be turning around. They cite hiring head coach Al Bagnoli in 2015, who was hugely successful as head coach at Penn, as an indication that Columbia "gets it" about football.

And of course, Columbia has come a long way. Both US News and Forbes 2022 college rankings place Columbia at Number 2 (or tied for Number 2) of the Best Universities in the nation. The acceptance rate to the College is now a staggering five percent. The first thing alumni from pre-1990 or so will tell you is, "If I applied now, I wouldn't get in." And they are almost always correct.

As 30-year admissions office veteran and former member James Minter said, in the early 1990s, the applications rate "took off," and has been rising ever since, as New York City got into much better shape and the College did a better job of selling its Core Curriculum.

"Columbia's fortunes are always tied to the city for good or for ill," offered Minter.

It is still a challenge recruiting football players to Columbia. The bus ride to practice at Baker Field is about 40 minutes each way (the walk to Powers Field at Princeton is about 10 minutes from the most distant point on campus, and to Harvard stadium a short walk across the Charles River) though most of the guys from the 1971 team didn't seem to mind ("I let off steam on the bus rides," recalled Jones) and Bagnoli is attracting players from all over the country, as a glance at the 2021 roster reveals.

And the outlook seems optimistic.

"The institutional support that was not there is now there," said Kaliades. "We've turned the corner. I think we can win another Ivy title."

NEW YORK—With six seconds left in the game, the cork was halfway out of the champagne bottle in the Columbia press box.

"It felt like the longest six seconds of my life," recalled long-time Columbia sports information director Kevin DeMarrais.

But when Princeton's kicker missed the 32-yard field goal attempt on October 2, 1971 at Baker Field, and the Lions won 22-20, Columbia's 26-year losing streak against their hated rival was over, and thus began the life of the "Cardiac Kids," the moniker DeMarrais was to give them for their seven straight games won or lost by three points or less in that storybook 1971 season, a record that was unmatched for 50 years in college football at the time.

"Over the years, we won the Rose Bowl, we lost to Princeton. We won the Ivy League title, we lost to Princeton," DeMarrais said, remarking on how big this first victory since 1945 over the tigers was.

"We were always confident we could win," said Frank Dermody, Columbia '73, a long-time leading Pennsylvania Democratic state legislator, and one of the three mega-talented linebackers on that 1971 team, said about the Princeton game, and the 6-3 '71 season.

Remember, this is a school with a less than fabled football tradition, that had come off of a 3-6 record the year before and a 1-8 season two years earlier, despite having been led by quarterback Marty Domres, a first-round NFL draft choice in 1969 (and just the most recent in a string of gifted Columbia quarterbacks that included Sid Luckman and Archie Roberts.)

And this was a Columbia University still reeling from the campus protests of spring 1968, the result of a volatile cocktail of anti-Vietnam War and anti-University administration feeling, that led to the occupation of Hamilton Hall and violent confrontations with police that received negative national media attention damaging to the University.

"It was total chaos trying to get back from '68," said Lila Coleman, widow of popular Dean of Students Henry Coleman, who was shot five times in his office, (but recovered), in 1972 by disgruntled student Eldridge McKinney – who has never been found.

In 1971, "Columbia was still limping along," remembered English professor and long-time associate Dean Michael Rosenthal.

And New York City, of course, is always inextricably linked to what Columbia is, and New York in 1971 was an exciting but not always safe place.

"I was held up at gunpoint near Ferris Booth Hall, and my room was broken into at my frat," recalled star quarterback Don Jackson, '73, a New York kid who had gone to the city's prestigious Stuyvesant High School. "But since I knew the city, for me it was business as usual."

For defensive back Steve Woods, '73, from Indianapolis, New York was more than he had hoped for. "There was so much going on culturally…you had Harlem, you had a plethora or museums. You got to meet James Baldwin…everyone came to campus."

Columbia sports, however, were a mixed bag. Basketball had been big on campus, with a nationally ranked team in 1969 led by future NBA star Jim McMillian and future Rhodes Scholar Heyward Dotson. But not football.

Football tight end Mike Jones, '72, recalled Dotson looking at him in the elevator one day and derisively saying, "You guys play football?"

The 1971 football team did more than a little to heal the wounds of 1968, and bring together the students, faculty, administration, (and even perhaps the city) in a time of nation-wide anti-war protests, emerging and long overdue but sometimes fitful gains for women, blacks and gays, and cultural changes not seen in decades – if ever.

Some Columbia Spectator headlines from the fall of 1971 give a pretty good idea of what was going on at the time:

Oct. 8 "Trustees consider election of woman to board vacancy" (no woman had ever been named to Columbia's board of trustees at that time)

Oct. 14 "Architecture panel considering Black as dean of school"

Oct. 15 "Latins to File Suit Against University

Nov. 3 "(Dean Carl) Hovde Affirms Position Opposing Gay Lounge"

Nov. 8 "Thousand Rally Against the War"

Nov. 15 "Women Asked to be Included in Negotiations on Sex Bias"

The '71 team was by a diverse group that was close then and has remained close for 50 years, many of whom had other options of where to play.

Middle linebacker Paul Kaliades, ' 73, from Snyder High School in Jersey City, who received a vote for the Heisman Trophy, got "full ride" offers from Nebraska, Syracuse and others. Co-captain John Sefcik, '72, from Ohio, turned down Princeton. Defensive backs Charlie Johnson, '72, another co-captain, and his Arsenal Technical High (Indianapolis) classmate Woods, could have gone to Purdue and the Naval Academy, respectively, though as Woods put it, "once you graduated from the Academy, your ass went straight to Vietnam." Quarterback Jackson, a skinny kid from Stuyvesant, turned down Notre Dame (and had come to Columbia because of Marty Domres. The attempt to tag Jackson with the nickname "Amsterdam Don," to compete with New York Jets QB Joe Namath's "Broadway Joe," as a nod to Columbia's other bordering avenue never quite caught on.)

(That class also featured a pretty good running back named Ed Harris, a friend of this author, who dropped out after two years, but seems to have fared well in his chosen career of acting, and another 1973 classmate, Eric Holder, who became US Attorney General under Barack Obama, Columbia '83.)

One thing they all shared in 1971 was the belief they were a talented team that could do anything.

"I went into that season thinking we had a good shot to run the table," remembered Kaliades.

"We were committed to one another," said Johnson, now retired from a career on Wall Street. "There were no challenges we could not meet. And we did."

The season didn't begin auspiciously, with a 3-0 loss to Lafayette, and for a moment, there was a "here we go again" feeling. Just for a moment.

But then came Princeton, a convincing, if nail-biting win, with Jackson connecting to (the late great) receiver Jesse Parks, '73 on key plays and defensive back Ted Gregory, '74, returning an interception 56 yards for a touchdown.

The following week was a heartbreaking two-point loss at Harvard, which several players blamed on the play calling of head coach Frank Navarro, who died this spring, and for whom there is little love lost among many of those interviewed for this piece.

Even in losing, things could be entertaining, with Columbia's famed band livening things up. James Minter, '73, a thirty year veteran of the admissions office and band member, recalled the band planned to take their pants off at a Harvard game, until someone said "You don't take your pants off at Harvard," but did fondly remember a "Martyr" halftime show where the band honored Joan of Arc by forming a French fry and playing the song "Light My Fire," always trying to get whatever they could past Dean Coleman, whose task was approving band scripts.

But on October 16, at Baker Field, the Cardiac Kids came roaring back.

Trailing 14-0 against Yale, the Lions surged in the second half thanks to a long kickoff return by Sefcik, and a touchdown pass from Jackson to Tom Hurley, '73.

With less than two minutes left, Jackson threw another TD pass, this time on a great one-handed catch by Bill Irish, '73.

Jackson had been calling offensive plays all season at this point, and called a two-point conversion play, an option pass to be thrown by the 5'7", 155 pound Sefcik – often the last man on the field in practice - to tight end Mike Jones.

Sefcik recalled Jackson saying to him before the play, "You better not screw it up, Mouse."

And he didn't, completing it to the wide-open Jones for the 15-14 last-minute victory.

Jackson called the Yale game "the most electrifying win," and calling Sefcik his "favorite player ever…nobody tougher," and that play for that two-point conversion "the crowning moment of my career," – quite a statement from a guy who was selected to the All-Ivy backfield with Cornell's Ed Marinaro, Yale's Dick Jauron and Princeton's Hank Bjorklund, as Jackson said, "three NFL guys and a skinny guy from New York."

The next week, Columbia beat Rutgers – again by one point – 17-16. It's hard to think of beating Rutgers as a footnote, but in the 1971 season, it was.

Then, they went to Cornell, to face the 5-0 Big Red, featuring the fearsome (future actor) Marinaro, who would finish second in Heisman Trophy voting that year, behind Auburn's Pat Sullivan (it's okay to say "Who?")

The Lions lost another close one, 24-21, as Marinaro rushed for 272 yards, breaking the then-standing NCAA rushing record. (Kaliades played with a fractured arm taped to his chest, but considering how strong Cornell was, Columbia kept it close.)

By now, fans were showing up at Baker Field. Not in droves, but showing up.

Eileen McNamara, Barnard '74, Journalism '76, a Pulitzer Prize winner and key figure in the Boston Globe's reporting on the Catholic priest molestation scandal, admits, "I probably didn't know Columbia had a football team," but she was a floor counselor and knew some players and that the team was successful in 1971, and began going to games.

Lyle Rexer, '73 a swimmer and Rhodes Scholar and transfer from the University of Michigan, said, "That team got me to go up to Baker Field…I liked watching them because it was the complete opposite of Ann Arbor."

Then Dartmouth came to town on November 6, sporting a 15 game winning streak and a lot of attitude.

Every communication to the Columbia players the week before that Dartmouth game started with the numbers "55-0," a bleak reminder of score of the 1970 game in Hanover.

Steve Woods recalled the 1970 game. "Every time they scored a touchdown, they shot off a cannon. There was so much smoke in the air, it looked like Waterloo."

The Lions all came in wearing white shoes as a morale booster, and brimming with confidence.

"We knew we could win against Dartmouth," said Mike Jones.

But it was a back and forth game, with the Lions leading 28-14 in the third quarter, only to see the lead disappear. Dartmouth went ahead 29-28.

Jackson marched the team down the field to set up a 34-yard field goal attempt by Kaliades with 48 seconds left.

Kaliades remembered saying to Jackson, who was also the holder on kicks, "Don't give me the f…ing laces" meaning the laces of the ball to kick, to which he said Jackson replied, "Shut up you fat f..k, just kick it."

As Jackson also noted, "most kickers come in with clean jerseys. Paul was beaten to death," having played the whole game at middle linebacker.

Kaliades made the field goal, a famous "wounded duck," that just cleared the cross bar, giving Columbia a 31-29 win – a story that made the front page banner headline of the New York Times sports section.

Columbia won their next two games by 14 and 18 points, finishing 6-3, third in the Ivy – not what they had hoped, but a long way from recent finishes.

"What I remember most about that season is we had so many heroes, so many stars," said sports information director DeMarrais, adding, "'71 helped us forget about '68."

Some of the guys were political during that era. Most weren't. George VanAmson, '74, a back-up player who described himself at 5'4" as "the smallest man in Ivy League football" his three years, and who later became a Columbia Trustee, said he was "very wary" of demonstrations on campus. "I was not a front line demonstrator, though I passionately agreed with it," noting that the "rich white kids" had other options if they got thrown out of school, but "I didn't."

Kaliades recalled a professor telling him "You are the first Columbia football captain who ever participated in shutting down a building here."

Nearly all the players have fond memories of that season, of their teammates, and of Columbia.

Going to Columbia was "the greatest decision I ever made, said John Sefcik.

"The Columbia brotherhood of football players is amazing. Columbia football is amazing," remarked Don Jackson.

"The Columbia backbone and bonds extend through generations."

"Even 50 years later, we still have that camaraderie," said Steve Woods, who noted that not long ago, Kaliades came to visit him in South Bend to see a Notre Dame football game.

"The greatest team in Columbia history was our team," offered Charlie Johnson, adding, "We brought excitement on Saturday afternoons in the fall," adding that being at Columbia was "One of the greatest experiences of my life."

Several of the players noted that institutional support for football was lacking when they played, but that seems to be turning around. They cite hiring head coach Al Bagnoli in 2015, who was hugely successful as head coach at Penn, as an indication that Columbia "gets it" about football.

And of course, Columbia has come a long way. Both US News and Forbes 2022 college rankings place Columbia at Number 2 (or tied for Number 2) of the Best Universities in the nation. The acceptance rate to the College is now a staggering five percent. The first thing alumni from pre-1990 or so will tell you is, "If I applied now, I wouldn't get in." And they are almost always correct.

As 30-year admissions office veteran and former member James Minter said, in the early 1990s, the applications rate "took off," and has been rising ever since, as New York City got into much better shape and the College did a better job of selling its Core Curriculum.

"Columbia's fortunes are always tied to the city for good or for ill," offered Minter.

It is still a challenge recruiting football players to Columbia. The bus ride to practice at Baker Field is about 40 minutes each way (the walk to Powers Field at Princeton is about 10 minutes from the most distant point on campus, and to Harvard stadium a short walk across the Charles River) though most of the guys from the 1971 team didn't seem to mind ("I let off steam on the bus rides," recalled Jones) and Bagnoli is attracting players from all over the country, as a glance at the 2021 roster reveals.

And the outlook seems optimistic.

"The institutional support that was not there is now there," said Kaliades. "We've turned the corner. I think we can win another Ivy title."

Highlights: FB | Columbia 29, Cornell 12

Saturday, November 22

Preview: FB | Coach Poppe - Week 10 | Presented by Amity Hall Uptown

Friday, November 21

Podcast: FB | Captains' Corner (S7, E10)

Thursday, November 20

Postgame: FB | Coach Poppe after Brown

Saturday, November 15